Proxy access by shareholders raises numerous issues and potential adverse effects on governance

The traditional view of corporate governance, anchored in law and customs, grants to the board of directors, once elected by shareholders, the responsibility of making all decisions in the interest of the corporation. That responsibility and accountability include, inter alia, appointing senior management and setting their compensation, declaring dividends, nominating board members for election, approving strategic orientations and budgets.

Recently, the prerogative to nominate the members of corporate boards, which has historically been the sole responsibility of incumbent directors, is now challenged by institutional investors determined to acquire the right, under certain conditions, to nominate their own candidates. The challenge to this board prerogative is called proxy access by shareholders to the director nomination process.

The SEC introduced new regulations in August 2010 which allowed shareholders holding at least 3 per cent of a public corporation’s shares, and having held these shares for at least 3 years, to propose nominees to the board (for up to a maximum of 25 per cent of the members of the existing board).

This new regulation was immediately challenged in the courts and had to be withdrawn when struck down. However, an amendment to the general regulation of shareholder proposals allowed shareholders to submit proposals on proxy access rules, which, if adopted by a majority of shareholders, were to be made part of the corporation’s by-laws.

This change provoked a tsunami of proposals from U.S. institutional investors calling for the right to put forth their own nominees for the board.

This access to voting proxies by shareholders is fast becoming a part of the governance landscape in the United States; it is very unlikely that major corporations will try to oppose the movement as institutional investors are fiercely supportive of this new “right.” However, the eventual impact of these initiatives on corporate governance remains to be assessed.

Corporations will try to preventively replace directors to avoid conflicts with large shareholders

In Canada, this issue has recently taken on a higher profile in the context of a consultation conducted by Industry Canada on the Canada Business Corporations Act (CBCA), one purpose of which was precisely to consider this issue of proxy access. All the institutional investors who expressed views came out in favour of greater access to the nominating process by shareholders, while the law firms and organizations representing the business community advocated against this initiative.

The Canadian Coalition for Good Governance (CCGG) recently issued a policy paper in favour of proxy access, taking a rather striking position as it shuns any minimum period of shareholding to obtain access to the nominating process. Thus, the CCGG policy position should provoke a vigorous debate on this issue in Canada.

Whatever the substance and merit of the arguments in favour of proxy access by shareholders, this initiative brings forth a host of issues related to the logistics of its application and the potential adverse effects on governance and board dynamics.

Among the arguments supposedly supportive of shareholder access to the nominating process, one is particularly noxious: the notion that “fear” among board members of being singled out for replacement would lead to higher level of board performance.

Indeed, the consequences for an individual director of being voted out of a board would be very significant and painful, both in economic and reputational terms; this is true for both incumbent nominees and the new nominees proposed by the shareholders.

Faced with the risk and arbitrary nature of a contested election, the directors would try to promote their personal contributions with institutional investors, thus generating an unhealthy competition among colleagues. In any event, how would the shareholders, called upon to choose between several nominees, decide for which nominee to vote, which nominee to dismiss when the voting proxy contains more nominees than available seats?

Will smaller institutional funds rely on proxy voting consultants (such as ISS or Glass Lewis), again increasing by tenfold their influence on the governance of public corporations? These proxy voting consultants will propose, as per their usual practice, some obvious, measurable criteria to make this choice: age of the directors, number of years as a member of the board, etc., which are, in fact, arbitrary criteria, uncorrelated with actual performance.

Once these criteria are well understood, it is likely that corporations will try to preventively replace directors to avoid conflicts with large shareholders and make rooms for their nominees. Therefore, directors would be shown the way out because they no longer satisfy the arbitrary criteria selected by proxy voting advisors without taking into account their actual contribution.

Even more likely, boards of directors will initiate discussions and negotiations with institutional investors who have indicated their intention to propose their own nominees in an effort to reach common ground; the result of such secret negotiations will often be that some of the nominees proposed by institutional investors will become the nominees of management, thus resulting in the forcible retirement of directors presumably viewed, more or less deservedly, as being weaker.

Moreover, the process may be hijacked. Groups of shareholders who champion specific causes (e.g., social, environmental or religious) may use this new “right” to nominate board candidates who espouse their priorities, to the possible detriment of other stakeholders of the corporation.

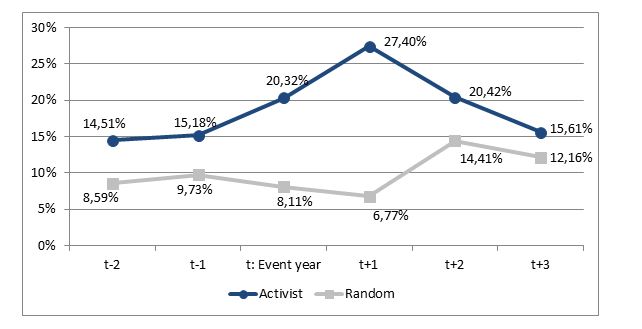

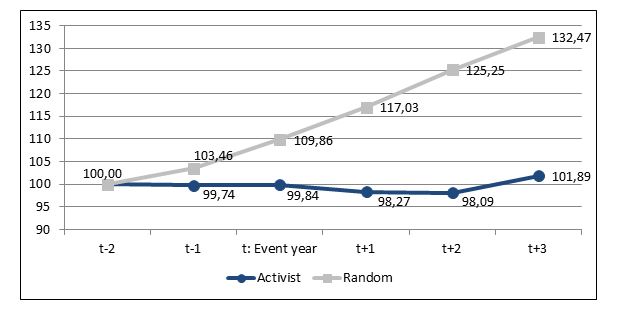

Obviously, if, as suggested by the CCGG, no minimum holding period were required for shareholders to be given access to the nomination process, that would open the door wide to “activist” hedge funds – or any other form of short-term investors. These funds could then play their usual games with great ease and at much lower costs than under their current business model. That would not benefit the long-term interests of Canadian corporations but may well benefit investors in the short term.

For such reasons, we contend that shareholder proxy access is ill-advised and may result in negative effects on governance practices.

We recommend that nomination committees of boards of directors implement a robust consultation process with the corporation’s significant shareholders and report in the annual Management Information Circular on the process and criteria adopted for nominating any new director.