With the Bombardier saga and the Couche-Tard warning bell, the usual litany of arguments against dual class of shares was again dusted off. Commentators opposed to this capital structure seem to forget or overlook the inconvenient truth that many of Canada’s industrial champions are controlled corporations often through a dual class of shares.

That is the conclusion one may draw from the Ontario Institute for Competitiveness and Prosperity study which identified 77 Canadian industrial champions; only 23 of them were widely-held corporations; 33 were listed controlled corporations, 19 of them via a dual class of shares; another 16 were privately held! (Flourishing in the global competitiveness game, working paper 11, September 2008). Furthermore, 23 of the 50 largest employers in Canada were dual class companies (Canada’s 50 biggest employers in 2012, Globe and Mail, June 28th 2012)

That is a fundamental point:

Without a controlling shareholder, without a dual class of shares, there would be no aeronautical industry in Canada, no C-Series to compete with Boeing and Airbus, a singular Canadian feat, no Magna in Ontario (a dual class company until 2010), no Rogers Communication, no Teck Resources, no Canadian Tire, no Weston, no CGI, no Shaw and so on.

And why is that?

In a period such as the 2002-2003 when the U.S. dollar was worth close to C$1.60 and the stock market was seriously depressed, all these Canadian companies would have been bargains for U.S. acquirers. Canada would have reverted to the branch-plant economy of the 1950s.

In any case, at one point or another, their success would have attracted foreign buyers. May we mention Tim Horton, Alcan, Falconbridge, etc. That is the reason why so many sensitive industrial sectors are legally protected in Canada from foreign takeovers (banks, telecoms, airlines, media companies)

And wisely so! For the Canadian regulatory context is one of the most hospitable to unwanted takeovers, much more so than in the United States. And don’t count on the toothless Investment Canada to block foreign acquisitions.

American companies have multiple measures (although waning in effectiveness) at their disposal to rebuff an unwanted takeover of their company (staggered boards, poison pills of unlimited duration, board’s authority to just say no, etc.) So, because of these American conditions, Boeing may carry on with its long-term investments without fear of an unwanted takeover in difficult times, and they have had quite a few.

Then, financial markets have become populated by short-term so-called investors and analysts fixated on the next quarter’s earnings per share and stock performance; they have become the locus of nasty financial games played with and around publicly listed companies.

Thus, the new breed of American (and Canadian) entrepreneurs not only do they want to be shielded from unwanted takeovers they also seek to insulate themselves from the quarterly pressures of analysts and short-term investors.

In 2015, according to Prosoaker Research (2016), 24% of all new share offerings (IPOs) in the U.S. were made with a dual class structure, a sharp increase from 15% in 2014 and 18% en 2013. So, young companies such as Alphabet (i.e. Google), Facebook, Groupon, Expedia, (and, in Canada, Cara, BRP, Shopify, Spin Master, Stingray) have issued two classes of shares, one with multiple votes which assures them of an unassailable control over their companies and makes them relatively indifferent to the short-term gyrations of earnings and stock price.

Furthermore, in Canada since 1987 (but not in the USA), companies issuing a class of shares with multiple votes must adopt, as a requirement to be listed on the Toronto stock exchange, a coat-tail provision. That provision essentially ensures that all shareholders will receive the same price for their shares, should the controlling shareholders decide to sell out. That twist, by itself, has removed most of the potential financial benefits of control through a dual class of shares.

Add to the mix of dual class companies the much stricter contemporary rules of corporate governance and the presence of a majority of independent directors on their boards and you have a recipe for success, for long-term strategic thinking, and for bold job-creating investments. It turns out to be a demonstrably optimal arrangement for all investors: controlling shareholders with their wealth at stakes managing, or supervising management, and taking a long-term view of the company.

Financial performance

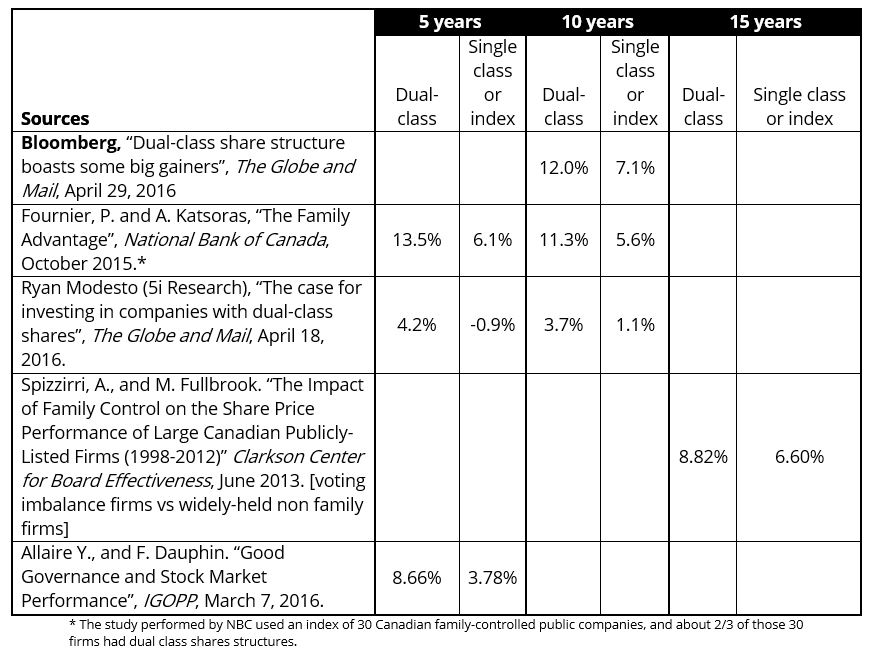

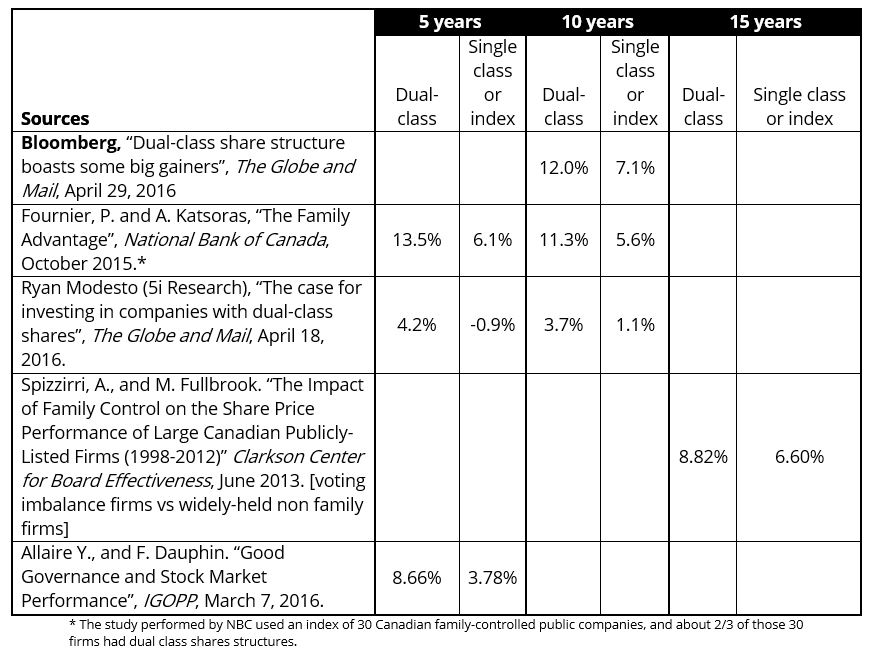

If getting good steady returns is what investors are looking for, dual class companies are indeed a good bet. The evidence is now pretty compelling that these companies perform better than conventional companies; or at least, perform as well and provide the added benefit of keeping their ownership and headquarters in the home country.

The following table provides some of that evidence from recent studies (but with different time periods):

Performance of Canadian dual class firms, compared to single class firms (or reference index) over 5, 10 and 15 years periods

Conclusion

Setting aside cases of extraordinarily attractive companies, such as Amazon where Bezos still owns 18% of the shares, it is difficult for companies to undertake gutsy investments and implement strategies unfolding over many years without some buffer from the short-term pressures of contemporary financial markets. That may not be to the liking of some financial players but so be it.

That pressing reality must be acknowledged by all, including policy makers, who do not have a vested interest in making lots of money quickly. Don’t be fooled by specious arguments merely disguising self-interest. Investors who would have bought a basket of shares in Canadian dual-class companies would have done well over the last ten years better than by holding shares in a portfolio of single-class companies.

Do not be swayed by the spurious argument of shareholder democracy. If shareholders were the equivalent of citizens in a democracy, then tourists (i.e. transient shareholders) would not vote and all new shareholders (i.e. immigrants) would have to wait for a considerable period of time before acquiring the right to vote.

Dual-class companies account for a good number of Canada’s industrial champions; indeed dual class shares are a pillar of our industrial structure. That ownership structure should be encouraged, promoted and blessed, provided proper safeguards are in place to protect minority shareholders.

Opinions expressed herein are strictly those of the author.