“History never repeats itself. Mankind always does.” – Voltaire

How did this unparalleled financial crisis come about? How can it be explained in simple terms? How can we learn from it and avoid making the same mistakes in future?

The problem – the direct cause of the crisis – can be traced to a series of cryptic abbreviations (CDO, CDS, VAR, MtM, etc.), which represent virtual financial instruments, off-balance-sheet deals, opaque transaction networks and so forth. The resulting context is so convoluted that coming up with a satisfactory explanation, one that is neither overly simplistic nor overly complex, is a virtually insurmountable pedagogical challenge.

“Explaining” the crisis

Part of the explanation – the easiest part to understand in fact – lies in the avarice of key stakeholders (including credit rating agencies) who succumbed to the lure of financial gain, the alignment of staggering compensation terms with short-term performance and extravagant rewards for hazardous management practices rooted in hidden or misunderstood risks. This Machiavellian greed for profit, although a constant throughout history, has evolved into a veritable moral crisis in the past 20 years.

Other more specific and more technical factors have also contributed to the onset and exacerbation of the crisis. Mark-to-market (MtM) accounting principles, which financial institutions are bound to put into practice, have had a major impact on the sequence of events leading up to the crisis. (See Allaire, Yvan, “La crise : un iceberg financier!”, La Presse, October 1, 2008.)

Flawed or patently absent regulations for new financial products and players, such as hedge funds (or, more accurately, speculative funds), have also helped inflate the credit and real estate bubble in the United States. From a regulatory perspective, this position was the manifestation of a kind of market ideology – one might even say market fundamentalism. Preached and practiced by Greenspan and others of his ilk, this fundamentalism is rooted in a rather touching faith in the markets’ ability to regulate themselves and rapidly and effectively correct any excesses or abuses that may arise.

This laissez-faire, come-what-may policy in the financial sector is inevitably a perilous approach and one that, in this case, has left a path of destruction in its wake. The unbridled growth of credit default swaps (CDSs), left unchecked, unchallenged and unaccounted for, is one of the leading (and technical) causes of the current crisis. This market, which in a few short years reached a nominal value of $55 trillion, has been prone to all kinds of schemes and scams from unscrupulous speculators and has served to conceal the global build-up of financial leverage. (For more on the subject of credit derivatives, see Allaire, Yvan, “Chronique d’une bulle financière,” Forces, Spring 2008)

Finance and mathematics

The mathematization of finance and investment over the past 30 years has also contributed subtly to the chaos of recent months. The massive influx of professionals trained in mathematics and physics into the financial instruments market (among the JP Morgans, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanleys and the like, not to mention hedge funds) has led to the emergence of “financial innovations” of an unprecedented level of complexity and abstraction as well as the development of risk assessment models capable of handling new financial products.

At first glance, these intricate statistical and mathematical systems are as impressive as they are intimidating for anyone without a PhD in the field, which is the case for most board members, fund managers and even credit rating agency professionals, despite the fact that the latter are the very individuals who should be able to understand the risks of these esoteric products in order to rate them appropriately. However, as precise as these quantitative risk assessment models appear to be, they ultimately hinge on flimsy assumptions and historical statistics that have little or no bearing on future performance.

Value-at-risk (VAR models) have played an increasingly key role in determining the amount of capital necessary to provide prudent support for an activity, the acceptable level of financial leverage and the appropriate returns for the degree of risk assumed.

These models attempt to estimate the likelihood that certain events or certain levels of loss will occur. This likelihood depends on the first historically observed volatility leader in relevant markets (“volatility” being financial-speak for “risk.”)

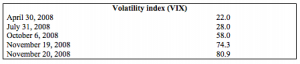

Using a simple example to illustrate, the following table shows the level of volatility of stock markets (in this case, the S&P 500) in a given index (VIX) since 1990. (The higher the index, the higher the volatility and risk):

To assess the level of risk incurred by an investment, analysis models use relevant data on the volatility of the type of investment over a five- or ten-year horizon. Accordingly, in early 2008, to assess an investment falling covered by the VIX index, the models would have taken into account the fact that the average volatility had been 15.5 for the previous five years and 20.2 for the previous ten years (including the turbulent dot-com bubble years and the aftermath of September 11, 2001).

It is important to note the very low volatility recorded between 2003 and 2007. This phenomenon has had a decisive influence on how risk, capital funding and maximum financial leverage have been determined. When volatility is this low, the risk involved in any kind of investment or debt is perceived as minimal.

However, investment professionals with a more critical mindset will require the risk assessment model to be subjected to what is known in financial circles as a stress test, in which it is exposed to data that is less favourable than that of recent years. In this example, the calculations would be redone, either using the worst results since 1990 (28.6 in 2002) or doubling the volatility observed in the past five years (2 x 15.5 = 31.0).

After conducting these tests and making decisions based on the findings, these professionals will conclude that they have acted with all due diligence. But have a closer look at the volatility rates for 2008:

Over a period of only few weeks in October and November, market volatility skyrocketed to a level nearly three times higher than the previous peak recorded since the index was created in 1990.

Risk calculations, the value of derivative products and the corresponding warranties, the capitalization required to support risk and debt, projected returns, credit premiums and other factors were thrown into disarray when volatility rates went through the roof.

Even the most sophisticated mathematical models failed to pick up on the warning signs (of which there were many) and interpret to what extent the behaviours they prompted would exacerbate the crisis. Like meteorologists riveted to their computer in a windowless room, the financial math whizzes kept on predicting fair weather while a financial hurricane was raging all around them.

“It is better to be vaguely right than precisely wrong,” said John Maynard Keynes. And wasn’t it Blaise Pascal, despite the fact that he was a mathematician, who claimed that intuition inevitably trumps logic?

What next?

The public must believe that this dysfunctional financial system can be changed and that it is not the inevitable outcome of incontrollable and irrepressible forces. It is a system developed and implemented by human beings. And one that human beings have the power to change.

Although it is true that stock markets around the world are all dropping dramatically, the fact remains that the Canadian financial and taxation systems are secure enough to help the country weather the brewing economic storm.

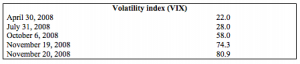

A concrete way of measuring Canada’s favourable position is, interestingly enough, by looking at the state of credit derivatives (or credit insurance) in various countries. The following table shows the cost (as of November 21, 2008) of purchasing insurance against credit defaults in various countries over the past five years:

The message is clear: the international markets see Canada as a better financial risk than any other country.

However, it is inappropriate to use the global financial crisis to advocate unrelated policies and measures. The federal finance minister, Jim Flaherty, is bordering on demagoguery when he holds up the crisis as a reason for creating a single securities commission in Canada. In actual fact, the countries that have been the most influential in and the most affected by this crisis, i.e., the United States and Great Britain, already have highly centralized securities commissions in place… to little or no avail!

Some concrete changes could help us avoid repeating (once again) the painful experience that we are currently enduring. Some of these suggestions have also been put forward by the Financial Stability Forum and mentioned in expert testimonies before a U.S. House of Representatives committee on November 13:

- Rein in out-of-control compensation. This is a problem we have not yet managed to resolve. And remuneration caps arbitrarily established by the state are not the solution (except in instances of a bailout, where a government invests directly in a company to save it from collapse). Our suggestion is simple: board members must be explicitly accountable for compensation paid to company executives, specialists and officers. They have the fiduciary responsibility for setting up a variable compensation system that is aligned with assumed risks, staggered over time and equipped with penalty clauses for non-performance. The recent example set by UBS can serve as a basic model in this regard. (For more information, see http://www.ubs.com/1/e/investors/compensationreport.html or Allaire, Yvan, “Fair Wages for an Honest Day’s Work,” Beyond Monks and Minnow by Yvan Allaire and Mihaela Firsirotu, Forstrat International Press, 2005).

It is just as important for institutional investors to stop pandering to the excesses of speculative funds. Ineffectual negotiating strategies and a lack of cooperation on the part of leading institutional funds have given rise to indecent levels of compensation for speculative fund managers. In fact, in 2007 the 25 highest-paid hedge fund managers (or more precisely speculative fund managers) together earned more than the top 500 CEOs (who already come under heavy fire for the “excessive” amount of money they earn!).

- Abolish over-the-counter transactions or, at the very least, decrease the volume and scope. It is baffling to think that the credit swap market could have grown at such a phenomenal rate and achieved a nominal value of $55 trillion in 2007, without any regulatory or supervisory mechanisms whatsoever in place to ensure transparency and identify the parties assuming the corresponding risks. Under a revamped system, when an OTC instrument reaches a certain volume, it would have to be converted into an appropriate stock market instrument and would thus be covered by a central compensation and disclosure mechanism.

- Review the role and methodology of credit rating agencies. These agencies have had too much influence over investors and lulled them into complacency. Moreover, motivated by handsome compensation from the very engineers of these complex financial instruments, credit rating agencies have been disposed to sanction products that have sometimes fallen outside their own realm of expertise. It is therefore high time to come up with compensation models that require credit agency users to pay for these services. Perhaps the major institutional funds should even create their own agency for derivative instruments and other complex products they tend to deal in. This agency would have to be staffed by qualified professionals capable of interpreting the complexities of the more intricately designed products on the market.

- Standardization of new financial instruments. The assumption that so-called “sophisticated” investors are adept at interpreting the finer points of the complex financial products that come their way does not hold. Often, risk control and regulatory mechanisms lag behind market “innovation.” In any other field, products that present a risk to public health or welfare are subject to an approval process before they are rolled out – for example, experienced travellers would never be called upon to weigh in on the safety of a new aircraft. New financial instruments should therefore be confidentially submitted to a body that is overseen by a securities commission or other entity, for the purpose of assessing risk and identifying the information that should be disclosed to buyers. This body should be independent and staffed by teams who are capable of assessing the risks associated with these new products.

- Reassess the latitude of pension funds in terms of alternative investments. Long subjected to a set of investment restrictions (i.e., caps on shares, foreign equity and real estate holdings), pension funds have gradually seen these conditions relaxed. As a result, pension funds have become the main backers of hedge funds and investment funds (i.e., privatization funds). Without the support of pension funds, these hedge and investment funds, both of which have played a definitive role in the market upheaval, would be much more limited in scope. For example, it turns out that 61% of the Blackstone privatization fund is financed by pension funds and foundations. For several reasons, including the dysfunctional way in which pension funds are assessed and compared on a yearly basis and the pressures to which they are subjected in order to satisfy performance obligations, pension funds have become avid investors in these new funds and leading buyers of these new esoteric products. It would therefore be useful to initiate a dialogue on how to curb this pursuit of the best corporate returns through alternative investments. As Paul Soriano so eloquently put it, “When events impact institutions, it’s generally because something has gone wrong.” And this financial crisis is, indeed, indicative of something that has gone very wrong!

Conclusion

It is true that people tend to learn slowly and forget quickly. It is true that financial fiascos never hit the same way twice. It is true that hastily or poorly designed regulations can do more harm than good. Nevertheless, not since 1929 has there occurred a crisis that has required such extensive public- and private-sector intervention. Doing nothing is simply not an option.

The purpose of this article is to provide a very rough idea of the causes of the financial crisis and to put forward a few recommendations to protect ourselves, even if only slightly, from repeated financial disasters.