The Economist’s activist hedge fund infomercial

Yvan Allaire | Financial PostWith its knack for tackling big subjects in a one-sided manner, The Economist in its February 7th issue imagines a dystopian world where corporate managers and boards of directors are generally incompetent, most investors are lazy; but “activists are a force for good”, “capitalism’s unlikely heroes” and “the saviours of public companies”!

Even for a paid commercial, ad people would have considered these claims a bit of a stretch. But in The Economist’s fantasy world, public companies are bureaucracies run by distant managers accountable to funds run by computers!!

On a topic requiring sober, balanced coverage, The Economist cuts logical corners, tramples contrary evidence, ignores a vast store of scholarship, and conjures up an empirical “study” to produce misleading data.

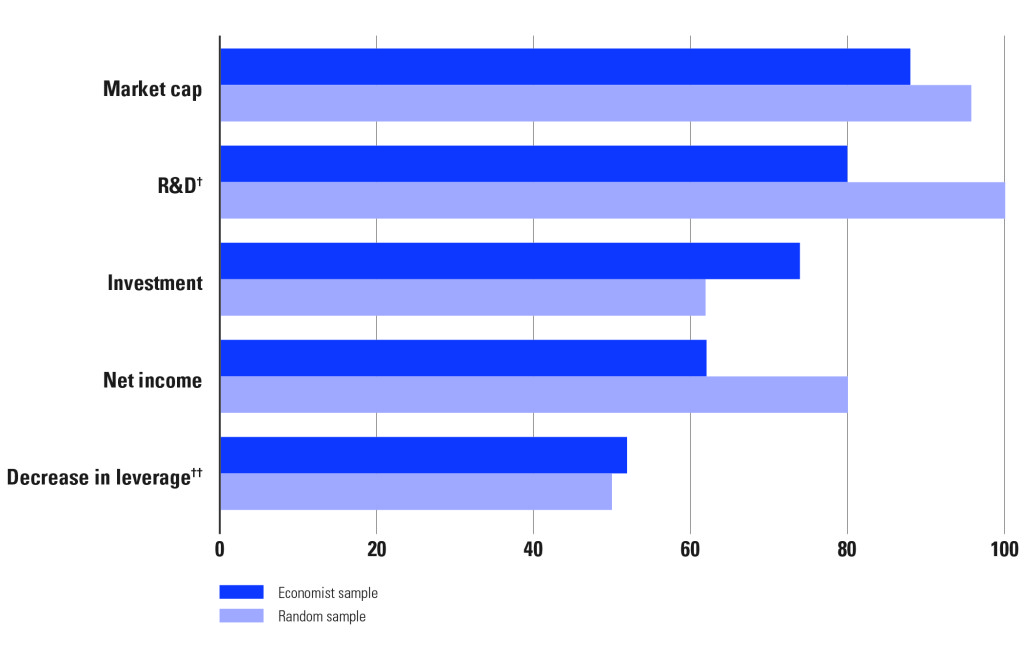

This so-called study consists of compilations, put together by The Economist, of the performance of the 50 largest activist positions taken since 2009! From this loose, ill-defined design, which raises a host of methodological issues, The Economist managed to produce its chart 4 showing how many of these 50 target firms (?) have shown improvement in market cap, R&D, investment, net income, and leverage between the fourth quarter of 2009 and the third quarter of 2014.

Astonished that such a poorly framed analysis would pass muster at The Economist, we undertook to carry out our own computations. What would be the performance of 50 randomly selected firms drawn from the S&P 500 over the same period?

Figure 1 herewith answers the question by juxtaposing the results of The Economist “study” and those of our random sample.

FIGURE 1

Top 50 activist-held companies* and a randomly picked sample** of 50 companies listed on the S&P500 index showing improvement, Q4 2009-Q3 2014, % of total.

* Source: The Economist, “Activist funds: An investor calls”, February 7th, 2015.

**IGOPP- Randomly picked companies from the S&P 500 index. Financial data provided by Compustat.

† 37 companies from our random sample do not disclose R&D expenses. We only kept the R&D companies for the improvement measure; The Economist does not state how many of their 50 companies are not disclosing R&D expenses.

†† Excluding financial companies.

On most measures of “performance”, our random sample does better than the top 50 activist-held companies! In other words, the analysis carried out by The Economist is worthless.

The Economist thus muddies the on-going debate about the pros and cons of hedge fund activism (See my piece “The case for and against activist hedge funds” at www.igopp.org). Sketching the most positive scenario of hedge fund activism, The Economist shows no interest in, or even awareness of, contrary evidence presented by those advocating restraint and control of these new players. Here are some of the many arguments against this breed of activism, which are either not mentioned or papered over in The Economist’s piece:

- Stealing from Peter to give to Paul. When activist hedge funds bring some lasting value for shareholders, it often takes the form of wealth transfer to shareholders from the company’s employees and debt holders rather than wealth creation. Several authors have documented the transfer of value from debt holders to shareholders as a result of hedge fund activism. Both Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s have warned about the debt downgrades likely to result from the sort of initiatives pushed unto companies by hedge funds.

- Their game is rigged for short-term pay-offs. They are in practice short-term players; they, and their academic supporters, argue that their interventions are not strictly speaking short-term in nature and that they do not cause long-term harm to companies; but their holding period as shareholder is fairly short (activist hedge funds held the shares for less than 15 months on average and for nine months or less in half the cases) and they have no reason to care or worry about what happens to companies once they have exited its stock. If they stick around longer, it is often because they have not found a profitable way out.

- Activist hedge funds live in a world with no other stakeholder than shareholders. They have little sympathy or patience for the view that companies should live by values other than short-term stock price, that companies are the situ of commitment, obligations and loyalty. If their myopic concept of the corporation were to become the norm for publicly listed companies, it would raise social and economic issues and lead many critics to question the legitimacy of these warped corporate entities.

- They create value mostly through financial engineering. Their playbook is essentially made up of a set of financial measures, well-known to boost stock prices for a short while. Even their request for board membership is but a first step to pressure the company to implement one or a combination of their standard financial moves: disburse all “excess” cash as shares buy-back or special dividends; split the company, spin-off or sell assets; sell the whole company.

- They are harbingers of dismal collective outcomes. Given the frequency of their attacks and their success rate lately, activist hedge funds instil fear in the management of many corporations; to forestall an attack, boards and management are counselled to examine their company as seen through the eyes of activist hedge funds and implement measures they would likely urge on the company’s management; as the number of activist hedge funds mushrooms, attracted by the immense pay-offs (and manageable risk) of this business, and companies pre-emptively adopt their short-term policies, the net overall effects could be quite toxic for a country’s industrial health.

The Economist seems to believe that this form of activism may fade away for lack of “preys”; i.e. poorly performing companies in need of these funds’ electroshock. Yet, the article reports that about a third of targeted companies “were outperforming the wider market”; but that “does not mean that it couldn’t do better”.

With that sort of logic and the blessing of The Economist, activist hedge funds will do a thriving business for a while longer.

What should be taken away from these arguments against “activist” hedge funds? The fact that many companies refuse to carry out the financial maneuvers urged on them by these activists may be an indication that their management and boards believe that they would jeopardize the company’s long-term interest if they gave in to the activists. Who is right? Why should it be assumed that boards are motivated by crass self-interest or afflicted with chronic incompetence but hedge funds are bearers of wisdom and acting in the superior interest of the company and all its shareholders?

These “activists” view corporations as mere properties, as a collection of assets to be traded, a narrow, soulless concept of the business firm. Whatever benefits this breed of activism may bring are outweighed by its negative impact on innovation and investment, on the ways companies are managed, on the support from critical stakeholders including society at large.

Opinions expressed herein are strictly those of the authors.

- Topics:

- Activism

- Hedge funds

- Stakeholders